One Million is the Average, Not the Max!

Simple Math Suggests a Simple Slogan for the WNBA Players as They Seek to Close the NBA's Gender-Wage Gap

The WNBA kicks off its 29th year this weekend and there are so many amazing stories to see this season. But as we watch the Minnesota Lynx win their 5th WNBA title (yes, that’s what the majority of people at ESPN said is going to happen!), there is another story hovering over the league. The players and the WNBA are going to have to renegotiate the WNBA’s collective bargaining agreement before the 2026 season begins. And it is not entirely clear the players and the league will reach an agreement.

Recently Alanis Thames of the Associated Press wrote the following article for detailing this labor dispute: “As WNBA popularity soars, player salaries remain a big hurdle for the league to address.”

Thames makes the following observation about upcoming negotiations:

Player salaries have been a longstanding point of contention between the NBA — which owns about 60% of the WNBA and leads CBA negotiations — and women’s basketball players. It’s one of the biggest financial hurdles the league still faces, and players have said they’re willing to sit out games if negotiations don’t lead to a pay structure they feel is fair.

“The talent is there, the product is there,” Dallas Wings guard Arike Ogunbowale said. “Now we need to be compensated for it.”

It is important to emphasize that WNBA players like Ogunbowale are very much negotiating with the NBA. The NBA has controlling interest over the WNBA and it is the NBA that calls the shots.

So when Bloomberg noted a few days ago that the WNBA players are only paid 10% of WNBA revenues (this is also noted in Slaying the Trolls), we know it is the NBA that ultimately bears responsibility for this outcome.

Alanis Thames (with a bit of help from me!) offered the following illustration about how little WNBA players are paid by the NBA today:

WNBA player salaries are also significantly less than what the NBA paid its players when it last generated around $30 million — $200 million today, when adjusted for inflation — in the early 1970s, said David Berri, an economics professor at Southern Utah University. It’s top players then were making around $300,000, which today would be roughly $2 million, he said.

“They’re paying the women today so very, very little relative to what they were paying the men 50 years ago,” Berri added, “and the explanation of that to me, (is) you’re obviously just treating the women differently than the men.”

Yes, back in the early 1970s – when the NBA was also nearing the end of its third decade – stars like Walt Frazier, Willis Reed, and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar -were actually paid more than WNBA stars like Napheesa Collier are paid today. And I don’t mean NBA stars got more fifty years ago once you adjust for inflation. I mean more in physical (i.e. nominal) dollars! The NBA had about 15% of the physical dollars the WNBA has today and still managed to find more dollars to pay their stars. When you do adjust for inflation, those NBA stars fifty years ago were getting more than $2 million per season.

That is very much what we would call a gender-wage gap!

The new collective bargaining agreement in the WNBA will very much raise the pay of the women the NBA employs to play basketball. The question is how much.

ESPN recently offered this estimate of the sort of increase WNBA players might be getting.

The headline for any new CBA will undoubtedly be increased salaries for players. The last renegotiation boosted the maximum salaries for stars from $117,500 in 2019 to $215,000 in 2020, with the cap jumping by more than 30% from $996,100 per team to $1.3 million. Larger increases are likely this time thanks to improved WNBA revenue streams.

One team source said it's possible max salaries could reach $1 million, which would be an increase of approximately 300% from the current $249,244 supermax and would imply a salary cap in the range of $4 million to $5 million per team.

The current maximum is less than $250,000. Maybe getting to $1 million sounds like a huge increase. But it most definitely does not solve the gender-wage gap in the NBA.

To see this, let’s do some simple math.

After expansion, there will be 16 teams in the WNBA. Given that the WNBA salary cap has historically been a hard cap (i.e. a team can’t exceed this number), then the WNBA – if this ESPN report is accurate – plans on spending $80 million per year on players ($5 million cap multiplied by 16 teams). Given that WNBA players are only getting about $20 million in revenue now, this seems like a huge increase.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem close to what the WNBA players think they should be paid.

Consider the following from a recent story by Bloomberg:

With its popularity surging, the league announced last July that it expected to collect $2.2 billion from an 11-year media rights deal with ESPN owner Disney, Amazon.com and NBCUniversal. Yet outside researchers estimate the players are paid an average of less than $150,000 each—totaling roughly 10% of league revenue, compared with 50% in the NBA. (The WNBA won’t comment on these estimates.) They’re not demanding NBA-level salaries, (Breanna) Stewart and other union leaders emphasize, just a revenue share closer to half, plus better benefits for family planning, child care and housing.

The WNBA players seem to want half of the league’s revenue. But $80 million is only half of $160 million. Right? And $2.2 billion divided by 11 is $200 million.

So, if the players get $80 million then that isn’t even 50% of the 11-year, $2.2 billion media deal.

For today, I am going to ignore the fact that it seems likely the WNBA’s media deal is worth far more than the $200 million per year the NBA apparently arbitrarily decided (and therefore, the WNBA is likely subsidizing the NBA going forward!). Taking this $200 million broadcasting deal at face value, it seems fairly clear WNBA revenues in 2026 are going to be far higher than $160 million. For example, it has been reported by Roberta Rodrigues the WNBA is getting $60 million more in additional media deals. The WNBA is also obviously selling tickets, merchandise, and making sponsorship deals. In 2023, Bloomberg said all revenue in the WNBA was $200 million. We know $60 million of that revenue in 2023 came from media deals. This means in 2023, everything else (tickets, merchandise, sponsorships, etc...) must have been about $140 million.

In 2024, ticket sales and merchandise exploded. It doesn’t seem unreasonable to argue when we consider all the sources of WNBA revenue, league revenue after this season will be between $400 million and $500 million. If the players get half, then they would be splitting between $200 million and $250 million. And with 16 teams, a salary cap between $12 million and $15 million makes more sense.

Or we can put it this way.

If there are 16 teams with 12 players each, the WNBA will be employing close to 200 players. If the WNBA players get half of the league revenue, the players will be splitting at least $200 million (i.e. half of $400 million). Therefore, the AVERAGE salary in the WNBA is at least $1 million ($200 million divided by 200 players).

So, the slogan for the WNBA players going forward is simple:

One Million is the Average, Not the Max!

At least, that has to be the slogan if the women of the WNBA are truly coming close to half of the revenue like the men of the NBA receive.

ESPN, though, says a source told them that the maximum might only be $1 million and the salary cap between $4 million and $5 million. I am guessing, though, the WNBA players are going to be able to do math a bit better than that source.

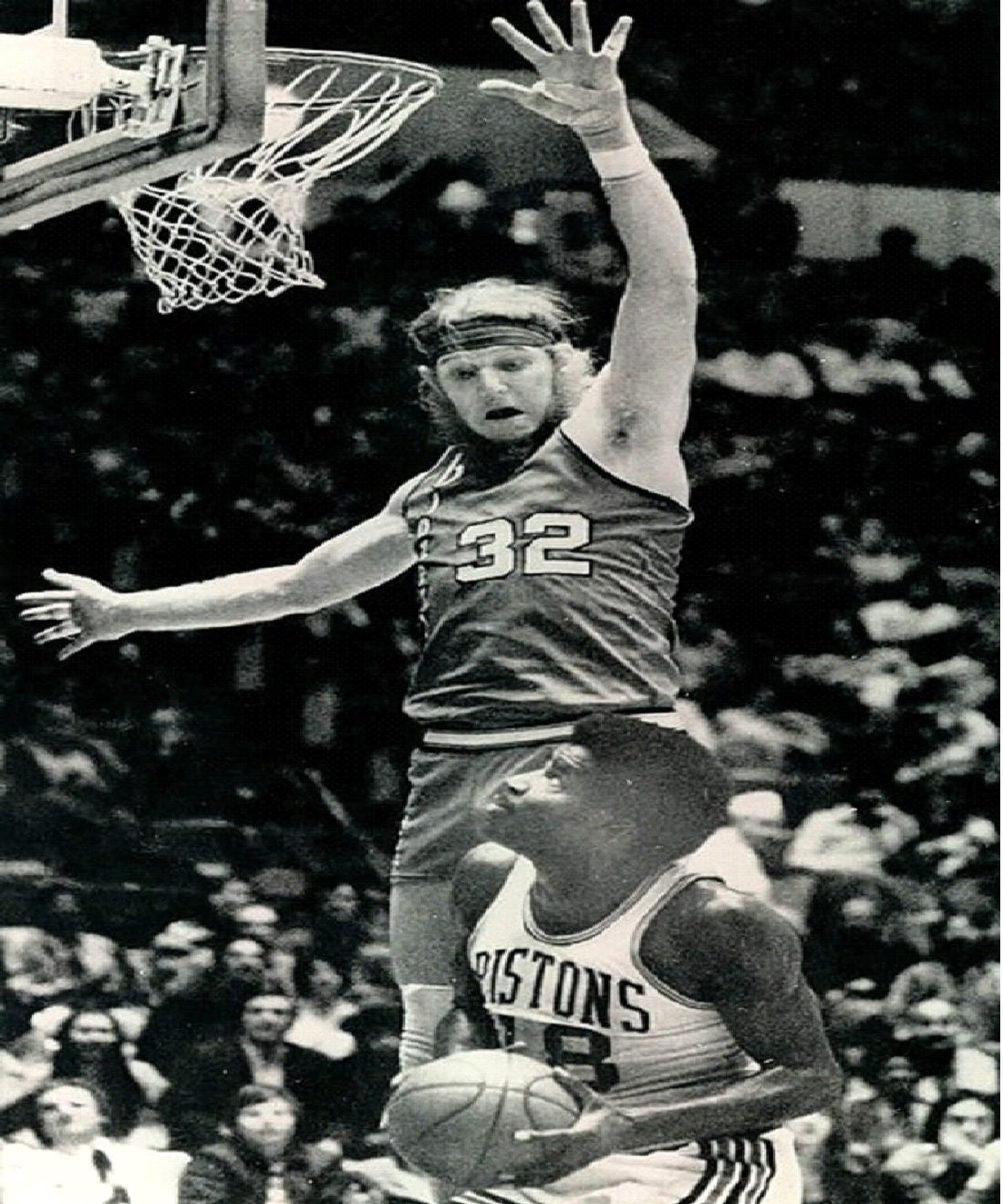

Beyond basic math, the WNBA should also teach the men of the NBA a bit of history. The first players in the NBA to be paid $1 million per year were Bill Walton and Moses Malone. This happened back in 1979-80. The NBA had less than $200 million in revenue at that time. We know this because they had less than $200 million in revenue in 1982-83.

Once again, the WNBA’s media deal itself is going to pay the league $200 million in 2026. So, the WNBA definitely has more money than the NBA had in the early 1980s. So, if the NBA can’t move the maximum past $1 million in the WNBA in 2026 — but they definitely could when the men had less revenue in the early 1980s — then we know gender-wage gap in the NBA will continue.

Yes, it is all just simple math!

So, are we going to get a 2026 WNBA season? It might require the WNBA players stand up and fight for it to happen. Fortunately – as Dr. Risa Isard argues – the players have lots of experience fighting for what is right.

Again, we return to the Thames article:

If players do decide to sit out games, Isard, the UConn professor, said it wouldn’t be surprising given their history of standing up for causes they believe in.

“Often, they’re really selfless in what those causes are,” Isard said, “and they’re looking out for everyone and anyone else and the community, and what is happening in the Senate race, and what’s happening in reproductive justice and what’s happening in gun legislation — so many ways that they stand up for so many populations across this country.

“And I guess when I hear them say, ‘We would consider that,’ What I hear them say is, ‘Why wouldn’t we stand up for ourselves? We stand up for everyone. So us, too.’”

These negotiations are likely going to be difficult. But WNBA players took down a U.S. Senator. How hard can it be to get the NBA to finally close its gender-wage gap?